Jenny "Henny" Schermann

(February 19, 1912 - May 30, 1942)

Listen to a human-read version of this section.

Jenny "Henny" Schermann was a Jewish lesbian born in 1912 to Russian immigrants. She worked as a salesperson in her family shoe store. In 1940, she was arrested for objecting to the law demanding all Jewish women adopt Sara as part of their name. The Nazis also noted that she was a “promiscuous lesbian.” She was deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp and subsequently murdered by gas at the Bernburg killing facility in 1942.

*****

This page tells the story of one person. Read this introductory essay for an overview of the history of the Nazis' persecution of LGBTQ+ people.

This essay was written by Natalie Peyton, the Pink Triangle Legacies Project’s 2024 Public History Intern in partnership with the Zucker/Goldberg Center for Holocaust Studies at the College of Charleston. It is based on the important research of the teams at the Stolpersteine Initiative in Frankfurt, Mapping the Lives, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Yad Vashem, and feedback from Dr. Javier Samper Vendrell. The audio version of this essay was provided by Claire Wimbush. Thank you for your work in preserving queer history.

Listen to a human-read version of this essay.

Jenny “Henny” Schermann was born to a Jewish family in Frankfurt, Germany, on February 19, 1912. Her father, Julius Chil Schermann, met his future wife, Selma, in Germany shortly after he immigrated from Russia. Henny was the family's eldest child, and she had two younger siblings: Herbert (1914 – 1942) and Regina (1916 – unknown). In 1931, Henny’s parents separated, leaving her mother, Selma, to take over the family shoe shop, which had been inherited from her parents. Henny worked as a salesperson for the shop, which was located on Meisengasse Street in Frankfurt.

Jenny went by “Henny,” which was a nickname used for girls but also sometimes for boys. This could suggest that Henny felt more masculine or ambiguous about her gender. It also indicates that others recognized and respected this by calling her Henny rather than Jenny. What we can say for sure, based on the historical evidence, is that Henny never got married, but she had a son named Walter with a non-Jewish man. At the same time, she was also a regular at lesbian bars in Frankfurt. Henny’s story helps us understand how the intersection of people’s multiple identities influenced the way they lived and the way the Nazis treated them.

In 1933, the Nazi rise to power meant that the authority of the German government could enforce the Party’s antisemitism. The Schermann family faced state-sanctioned discrimination and persecution because they were Jewish. For example, Henny’s sister was not allowed to legally marry her spouse, a non-Jew, due to the Nazis' Nuremberg Race Laws. This meant that their son was considered illegitimate by the government.

The Schermanns’ livelihood, too, was drastically affected. The Nazis implemented a nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses on April 1, 1933. The boycott ultimately only lasted one day, but as antisemitism became German policy under Nazi rule, economic pressures grew. In 1935, the Schermanns were forced to close their family’s business. Afterward, Henny worked for other companies as a salesperson.

In an attempt to further separate German Jews from the rest of German society, the Nazis passed the Law on Alteration of Family and Personal Names in August 1938. It forced Jewish people with “non-Jewish” names to add Jewish names to their legal names (“Israel” for men and “Sara” for women). After 1938, Henny was documented for refusing to add “Sara” as part of her first name in official identification documents.

Henny’s refusal to add the name ‘Sara’ to her documentation symbolizes her commitment to personal autonomy and rejection of the Nazis’ antisemitic policies.

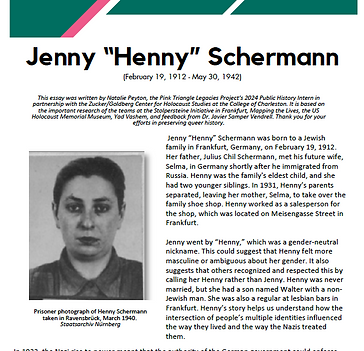

Upon her arrest, her Prisoner ID and Certificate of Incarceration classified her as Jewish and a political opponent. The Nazis also knew she was a lesbian and noted that on her documents. On January 3, 1940, the Nazis deported Henny to the Ravensbrück concentration camp for women. Her uniform’s badge consisted of two yellow triangles, identifying her as Jewish to camp officials and other prisoners.

US Holocaust Memorial Museum

Arolsen Archives

US Holocaust Memorial Museum

US Holocaust Memorial Museum

On the back of her camp mugshot, Ravensbrück official Dr. Friedrich Mennecke, wrote:

“Jenny Sara Schermann, born February 19, 1912, Frankfurt am Main. Unmarried shopgirl in Frankfurt am Main. Licentious lesbian, only visited such bars. Avoided the name ‘Sara.’ Stateless Jew.”

As historian Dr. Anna Hájková has demonstrated, an intersectional approach helps us understand the fate of queer women like Henny. While the Nazis used multiple different laws to arrest queer women, they did not explicitly criminalize lesbian relationships. Paragraph 175, the national anti-gay law that the Nazis strengthened in 1935, applied only to men. Therefore, a lesbian’s sexuality was rarely the only reason for being arrested. But it is clear that Henny’s dual identity as Jewish and lesbian played a defining role in how the Nazis treated her.

While at Ravensbrück, Henny was selected for murder as part of the 14 [F] 13 policy, which authorized the SS camp officials to kill sick or infirm prisoners. Records indicate that she was gassed on May 30, 1942, at the Bernberg Euthanasia Center, a former psychiatric facility that specialized in the systematic murder of “asocials” in society.

Of Henny’s family, only her father, her son, and her nephew survived the Holocaust. Her mother, Selma, and sister, Regina, were deported to the Lodz ghetto in 1941. There is currently no information about their fates. They were likely murdered or died within the ghetto without documentation. Her brother, Herbert, tried to escape but was captured in France and deported to Auschwitz, where he reportedly died of “sudden cardiac death” in 1942. Although Henny’s father, Julius, survived the horrors, he passed away in 1948 due to causes related to his persecution.

On May 9, 2010, Henny, Selma, Regina, and Herbert Schermann were honored by four Stolperstein memorials placed at the location of their family shoe shop in Frankfurt. Regina’s son, Max Meir Schermann Sherman, was instrumental in this process as an advocate for his family. His paternal grandparents, who were non-Jews, hid him until the end of the war, when his father was able to claim him.

Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, has recorded the names and fates of survivors and victims since its establishment in 1953. As part of these efforts, Yad Vashem accepts pages of testimony, Survivors/refugees forms, and other documentation to record the lives of victims. Since 2012, Henny’s nephew, Max, has submitted four Pages of Testimony to Yad Vashem. and two Survivor/ Refugee registration forms dedicated to remembering and honoring the fates of his family. These records stand as an invaluable testament to the strength of remembrance.

Sources & Further Reading

City of Frankfurt am Main, “Schermann, Henny, Herbert, Regina and Selma.” Initiative Stolpersteine Frankfurt am Main.

Samuel Clowes Huneke, “Heterogeneous Persecution: Lesbianism and the Nazi State,” in Central European History 54, no 2 (June 2021): 297–325.

Mapping the Lives - A Central Memorial for the Persecuted in Europe, 1933-1945: “Henny Schermann.”

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Henny Schermann” Holocaust Encyclopedia.

Yad Vashem, “Henny Jenny Sara Schermann,” Page of Testimony Collection.

For Citation

Natalie Peyton, "LGBTQ+ Stories from Nazi Germany: Henny Schermann." (2024) pinktrianglelegacies.org/schermann

(Updated Dec. 2024)